I. Introduction

With the Lundbeck Decision, the European Commission (the “Decision” and the “Commission,” respectively) ended its ten-year investigation on reverse payment settlements and found that the Danish pharmaceutical company, Lundbeck, and four generics producers had concluded anticompetitive agreements, in breach of Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (the “TFEU”).[1] According to the Commission, this would have allowed Lundbeck to keep the price of its drug citalopram artificially high and delay the entry of cheaper medicines into the EU market.[2]

On 8 September 2016, the EU General Court (the “General Court”) confirmed that certain pharmaceutical “reverse payment settlements” can constitute a breach of the EU antitrust rules (the “Ruling”).[3] Under the so-called “reverse payment settlement agreements”, an original pharmaceutical manufacturer, or “originator”, settles an IP challenge from a manufacturer of generics by paying the latter to stay out of the market.

II. Background

Lundbeck is “a global pharmaceutical company specializing in psychiatric and neurological disorders”.[4] These include medicinal products for treating depression.[5] From the late 1970s, Lundbeck developed and patented an antidepressant medicinal product containing the active ingredient citalopram’.[6]

After its basic patent for the citalopram molecule had expired, Lundbeck only held a number of the so-called “process” patents, which, according to the Commission, provided only “a more limited protection”.[7] In particular, Lundbeck had filed a salt crystallisation process patent.[8]

According to the Commission, in 2002, Lundbeck concluded six agreements concerning citalopram with four entities active in the production or sale of generic medicinal products, namely Merck KGaA / Generics (UK), Alpharma, Arrow, and Ranbaxy. Always according to the Commission, in return for the generic undertakings’ commitment not to enter the citalopram market, Lundbeck paid them substantial amounts.[9] In addition, Lundbeck purchased stocks of generic products for the sole purpose of destroying them, and offered guaranteed profits in a distribution agreement.[10]

In October 2003, the Commission was informed of the existence of the agreements at issue by the Konkurrence- og Forbrugerstyrelsen (the “KFST”, the Danish authority for competition and consumers).[11] The Commission took over the case and, by the decision of 19 June 2013, made the following findings: (i) Lundbeck and the generic undertakings were at least potential competitors;[12] and (ii) the agreements at issue constituted restrictions of competition by object, in breach of the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements provided under Article 101 TFEU.[13] The Commission imposed a total fine of €93.7 million on Lundbeck and € 52.2 million on the generic undertakings. The Commission took into consideration the length of its investigation (almost ten years) as a mitigating circumstance which led to fine reductions of 10%.[14] Lundbeck and the generic undertakings brought actions before the General Court, seeking the annulment of the Commission’s decision. The Court dismissed the actions brought by Lundbeck and the generic undertakings and confirmed the fines imposed on them by the Commission.[15]

After the Lundbeck case, in 2013 and 2014, the Commission imposed fines on companies in two other reverse settlement investigations – one concerning fentanyl, a pain-killer[16], and the other concerning perindopril, a cardiovascular medicine.[17] The Fentanyl decision was not appealed. Several appeals against the Servier decision are pending before the General Court.[18] In 2016, in the Paroxetine Investigation, the UK Competition and Market Authority (“CMA”) issued infringement decisions to a number of companies regarding ”pay-for-delay” agreements over the supply of an antidepressant.[19] These agreements were found to be an infringement by object and effect. In March 2017, the CMA issued a statement of objections relating to an agreement aimed at delaying the entry into the market for the supply of Hydrocortisone tablets. The CMA has not yet issued its final decision.[20]

In addition, since 2009, the Commission has been continuously monitoring patent settlements in order to identify settlements which it regards as “potentially problematic” from an antitrust perspective, namely those that limit generic entry against a value transfer from an originator to a generic company. The latest report was published in December 2016.[21]

III. The Ruling

First, like the Commission, the Court analysed whether Lundbeck and the generic manufacturers concerned were indeed potential competitors at the time the agreements at issue were concluded.[22] The General Court made the following findings in this regard:

In order for an agreement to restrict potential competition, it must be established that, had an agreement not been concluded, the competitors would have had “real concrete possibilities” of entering that market.[23] The Court held that the Commission had carried out a careful examination, as regards each of the generic undertakings concerned, of the real concrete possibilities they had of entering the market. In doing so, the Commission relied on evidence such as the investments already made and the steps taken in order to obtain a marketing authorisation[24]

Moreover, the Court noted that in general, the generic undertakings had several real concrete possibilities of entering the market at the time the agreements at issue were concluded.[25] Those possible routes included, inter alia, launching the generic product with the possibility of having to face infringement proceedings brought by Lundbeck (i.e., the so-called launching ‘at risk’).[26] More precisely, the General Court was of the view that “the presumption of validity cannot be equated with a presumption of illegality of generic products validly placed on the market which the patent holder deems to be infringing the patent”.[27] Consequently, the Court, continued, “’at risk’ entry is not unlawful in itself”.[28]

As rightly noted by commentators, these considerations introduce a further layer of complexity in the already intricate relationship between EU Competition law and IP law. In addition, since the right to exclude lies at the core of any IP right and (if there is no competing product) to have a monopoly is not illegal, unless it is attained or maintained by improper means,[29] it can be argued that the Commission’s findings infringes Article 345 TFEU, according to which “[t]he Treaties shall not prejudice the rules in the Member States governing the system of property ownership”. Thus, Ibañez Colomo has noted that “Lundbeck departs from the principle whereby an agreement is not restrictive by object where it remains within the substantive scope of an intellectual property right”.[30] This principle would derive from the Erauw-Jacquery,[31] Coditel II,[32] BAT v. Commission[33] and Nungesser[34] rulings of the ECJ. Ibañez Colomo’s point becomes particularly clear at para. 335 of the (Lundbeck) Ruling where the General Court expressly noted that “even if the restrictions set out in the agreements at issue fall within the scope of the Lundbeck patents – that is to say that the agreements prevented only the market entry of generic citalopram deemed to potentially infringe those patents by the parties to the agreements and not that of every type of generic citalopram – they would nonetheless constitute restrictions on competition ‘by object’ since, inter alia, they prevented or rendered pointless any type of challenge to Lundbeck’s patents before the national courts, whereas, according to the Commission, that type of challenge is part of normal competition in relation to patents (recitals 603 to 605, 625, 641 and 674)”.[35]

Second, the Court analysed whether the Commission was entitled to conclude that the agreements at issue constituted a restriction of competition by object, a point to which we will turn next.

IV. Conclusions: On Reverse Payments as Restrictions of Competition by Object

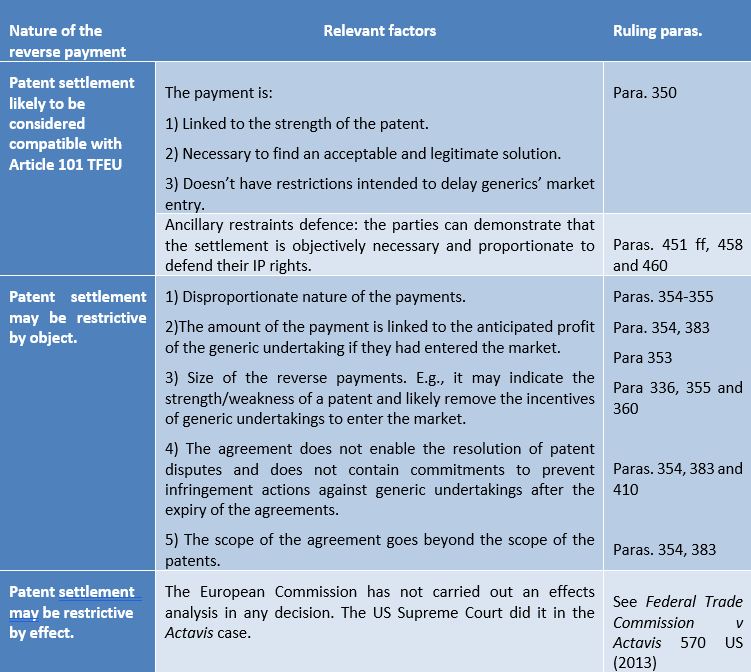

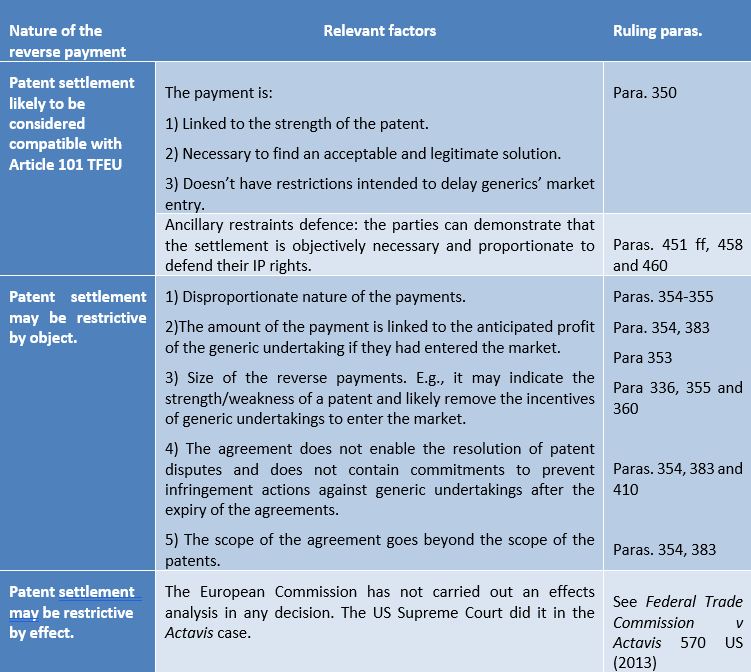

The Lundbeck ruling brings a number of what Donald Rumsfeld would probably refer to as “known unknowns”, that is things we know we do not know, in relation to reverse payment settlements.[36] Indeed, the findings of the Lundbeck ruling can be summarised as follows (see also the table below):

- There are certain patent settlements which are likely to be considered compatible with Article 101 TFEU. This is the case of settlements:a. In which, in the words of the General Court, “(i) payment is linked to the strength of the patent, as perceived by each of the parties; (ii) [payment] is necessary in order to find an acceptable and legitimate solution in the eyes of two parties and (iii) [payment] is not accompanied by restrictions intended to delay the market entry of generics”.[37]

The inclusion of the word “and” is worrying. The requirements set out in the preceding paragraph should be alternative and not cumulative. Otherwise for a settlement to be lawful it must not delay entry (which probably is enough, in and of itself, to avoid the antitrust concern, namely, a delayed entry of generics) and it must be necessary (i.e., it probably needs to meet the requirements of an ancillary restraints defence, more on which below) and the payment might be linked to the strength of the patent “as perceived by each of the parties”. Such an intrinsically subjective requirement appears to the writer as particularly complicated to administrate and at odds with the objective nature of Article 101(1) TFEU. It would appear that the Court is encouraging conversations such as the following: “let’s settle, but only if we can ensure the settlement reflects (and comes across as reflecting) your and my perception of the strength of the patent (and a number of other cumulative requirements my lawyers and I need to meet), otherwise we might have an antitrust concern”.

b. Qualifying for an ancillary restraints defence. e., settlements in relation to which the parties to the settlement (for the burden of proof will be on them) can demonstrate they are objectively necessary and proportionate in order to defend their IP rights.[38]

- There are certain patent settlements which are likely to be considered incompatible with Article 101 TFEU as restrictions of competition by object. The ruling is not particularly clear in this regard.a. A literal reading of paragraph 334 of Lundbeck could potentially make “problematic” each patent settlement “where they [provide] for the exclusion from the market of one of the parties, which was at the very least a potential competitor of the other party, for a certain period, and where they were accompanied by a transfer of value from the patent holder to the generic undertaking liable to infringe that patent (‘reverse payments’).”

b. A more holistic reading of Lundbeck would confine the Commission’s finding to the facts of the case. Even though it is difficult to pinpoint what the court considered to be the decisive factors when stating that a reserve settlement constituted a restriction by object, the following factors appear to have been relevant:

- The allegedly “disproportionate nature” of such payments “combined with other factors, such as the fact that the amounts of those payments seemed to correspond at least to the profit anticipated by the generic undertaking”.[39] Referring to the US Supreme Court ruling in Actavis,[40] the Court indicated that “the size of a reverse payment may constitute an indicator of the strength or weakness of a patent”.[41] According to the Commission “the higher the originator undertaking estimates the chance of its patent being found invalid or not infringed, and the higher the damage to the originator undertaking resulting from successful generic entry, the more money it will be willing to pay the generic undertaking to avoid that risk”.[42]

- Indeed, the correspondence between the amount of the payment that seemed and the profit anticipated by the generic undertakings if they had entered the market.[43] According to the Commission “the value which Lundbeck transferred, took into consideration the turnover or profit the generic undertaking expected if it had successfully entered the market”. [44]

- The absence of provisions allowing the generic undertakings to launch their product on the market upon the expiry of the agreement without having to fear infringement actions brought by Lundbeck.[45]

- The presence in those agreements of restrictions going beyond the scope of Lundbeck’s patents,[46] such as restrictions with regard to citalopram products that could have been produced in a non-infringing manner.[47]

- According to the Court, “the agreement at issue transformed the uncertainty in relation to the outcome of such litigation into the certainty that the generics would not enter the market which may also constitute a restriction on competition by object when such limits do not result from an assessment, by the parties of the merits of the exclusive right at issue, but rather from the size of the reverse payment which, in such case, overshadows that assessment and induces the generic undertaking not to pursue its independent efforts to enter the market”.[48] The generics thus no longer had an incentive to continue their independent efforts to enter the market.[49]

- There are certain patent settlements which (presumably) are considered to be incompatible with Article 101 TFEU as restrictions of competition by their effects. Hic sunt dracones. More precisely, given that none of the pay-for-delay decisions dealt with by the Commission conducted an effects analysis, we are left without guidance as to how that analysis will be conducted. Again, a known unknown. The Commission’s ten-year investigation on reverse payment settlements has not shed light to how to conduct an effects analysis under Article 101(1) TFEU. We are left, perhaps, with the findings of the US Supreme Court in Actavis, according to which, “the likelihood of a reverse payment bringing about anticompetitive effects depends upon its size, its scale in relation to the payer’s anticipated future litigation costs, its independence from other services for which it might represent payment and the lack of any other convincing justification. The existence and degree of any anticompetitive consequences may also vary among industries”.[50]

Moreover, to the extent that the case for restrictions of competition by object is administrability, this author cannot but note that the Lundbeck ruling does not constitute a positive evolution. The General Court noted that “it is established that certain collusive behaviour […] may be considered so likely to have negative effects, in particular on the price, quantity or quality of the goods and services, that it may be considered redundant, for the purposes of applying Article 101 TFEU to prove that they have actual effects on the market”.[51] However, the Decision has 464 pages. Given that the Fentanyl and Servier decisions occupy 147 and 813 pages, respectively, in investigations that lasted for almost ten years, 27 months and 5 years (again, respectively), one cannot but wonder whether the Commission’s resources would have been better spent analysing the actual effects of the agreement and not defending a legal category.

[1] Commission Decision C(2013) 3803 of 19 June 2013 relating to a proceeding under Article 101 [TFEU] and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement, Case AT.39226 — Lundbeck (the “Decision”).

[2] See European Commission Press Release IP/13/563, of 19 June 2013, available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-563_en.htm?locale=en

[3] See T-472/13 Lundbeck v. Commission [NYR] (the “Ruling”), of 8 September 2016.

[4] See, for more detail, http://www.lundbeck.com/global/about-us.

[5] See Ruling, at para. 1.

[6] See Ruling, at para. 16.

[7] See European Commission Press Release IP/13/563, 19 June 2013, available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-563_en.htm?locale=en. It should be recalled, in this regard, that, according to Article 27 of the TRIPS (WTO) Agreement, “patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application“.

[8] See Ruling, at para. 20.

[9] See Ruling, at paras. 26; 35; 39; 42-43 and 47-48.

[10] See Ruling, at para. 26; 35; 39; 42-43; 47-48.

[11] See Danish Competition and Consumer Authority Press Release 1120-0289-0039/VIS/SEK, 28 January 2004 , available at: http://www.kfst.dk/Afgoerelsesdatabase/Konkurrenceomraadet/Styrelsesafgoerelser/2004/Undersoegelse-af-Lundbeck?tc=E538038EB1E04A96B9964BE4C0F85F46 (Only available in Danish)

[12] See Decision at paras. 610 ff.

[13] See Decision at paras. 647 ff.

[14] See Decision, at paras. 1306, 1349 and 1380.

[15] See Ruling, Operative part.

[16] See European Commission Press Release IP/13/1233, Commission fines Johnson & Johnson and Novartis € 16 million for delaying market entry of generic pain-killer fentanyl, 10 December 2013, available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-1233_en.htm.

[17] See European Commission Press Release IP/14/799, 9 July 2014, Commission fines Servier and five generic companies for curbing entry of cheaper versions of cardiovascular medicine, available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-799_en.htm.

[18] See Case T-147/00 Laboratoires Servier v Commission.

[19] See Case CE/9531-11 Paroxetine, 12 February 2016. For a comment on the case see Ezrachi, A., EU Competition Law: An Analytical Guide to the Leading Cases, 5th Edition, Bloomsbury, 2016, 396

[20] See CMA Press Release of 3 March 2017, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-alleges-anti-competitive-agreements-for-hydrocortisone-tablets. See also Nathalie Ska, Philipp Werner, and Christian Paul, “Pay-for-delay Agreements: Why the EU Should Judge them by their Effects”, Oxford Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 3 May 2017.

[21] See, European Commission, “7th Report on the Monitoring of Patent Settlements (period: January-December 2015)”, 13 December 2016, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/pharmaceuticals/inquiry/patent_settlements_report7_en.pdf

[22] See Ruling. The General Court separately analysed each agreement. See, inter alia, in relation to Lundbeck and Merck, para. 225; in relation to Lundbeck and Arrow, paras. 266-270, in relation to Lundbeck and Alpharma, para. 290 and, in relation to Lundbeck and Ranbaxy, para. 330.

[23] See Ruling, at para. 100. See further Case T-360/90 E.ON Ruhrgas and E.ON v Commission, at para. 86.

[24] See Ruling, at para. 131.

[25] See Ruling, at para. 97. See further Decision, at para. 635.

[26] See Ruling, at paras. 121.

[27] See Ruling, at paras. 97.

[28] See Ruling, at para. 122.

[29] See David J. Teece and Edward F. Sherry, “On patent monopolies: An economic re-appraisal”, CPI Antitrust Chronicle April 2017, available at: https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/CPI-Teece-Sherry.pdf.

[30] See Ibañez Colomo, P., “GC Judgment in Case T-472/13, Lundbeck v Commission: on patents and Schrödinger’s cat”, at Chillin’ Competition, 13 September 2016, available at: https://chillingcompetition.com/2016/09/13/gc-judgment-in-case-t-47213-lundbeck-v-commission-on-patents-and-schrodingers-cat/.

[31] See Case 27/87 SPRL Louis Erauw-Jacquery v La Hesbignonne SC, of 19 April 1988.

[32] See Case 262/81 Coditel SA, Compagnie generale pour la diffusion de la television, and others v Cine-Vog Films SA and others, of 6 October 1982.

[33] See Case 35/83 BAT Cigaretten-Fabriken GmbH v Commission, of 30 January 1985.

[34] See Case 258/78 Nungesser v Commission, of 8 June 1982.

[35] See Ruling, at paragraph 335.

[36] See Rumsfeld, D., Known Unknown: A Memoir, Sentinel, 2011.

[37] See Ruling, at para. 350.

[38] See Ruling, at paras. 451 ff, in particular, at paras. 458 and 460.

[39] See Ruling, at paras. 354; 355.

[40] See Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis, 570 US (2013).

[41] See Ruling, at paragraph 353.

[42] See Decision, at para. 640.

[43] See Ruling, at paras. 354; 383; 414.

[44] See Decision, at paras. 6; 788; 824; 874; 962; 1013; 1087.

[45] See Ruling, at paras. 354; 383; 410.

[46] See Ruling, at paras. 354; 383.

[47] See Decision para. 693.

[48] See Ruling, at para. 336.

[49] See Ruling, at paras. 355; 360.

[50] See Federal Trade Commission v Actavis 570 US 2013.

[51] See Ruing, at para. 341.