A clinical trial on healthy volunteers sponsored by Portuguese pharmaceutical company Bial came to an abrupt halt in early January 2016, when one of the trial participants was declared brain dead and five others were hospitalised soon after with organ failure and suspected brain damage. The trial drug, BIA–102474–101, was intended to target a range of diseases including pain relief. It was being tested in humans for the first time. French contract research organisation BioTrial (“CRO”) had been engaged by Bial (the “Sponsor”) to manage and host the trial at its Rennes trial centre, in France. The tragic outcome raises questions for organisations involved in sponsoring or conducting clinical trials, and is likely to lead to further reform of the clinical trials regulatory regime across the EU.

The legal framework for clinical trials in the EU

Clinical trials involving medicinal products for human use are governed in the EU by Directive 2001/20/EC (the “Clinical Trials Directive”). This framework legislation provides for additional implementing directives and guidelines. It also provides that an application for a Clinical Trials Authorisation (“CTA”) must be made to the national Competent Authority of any member state in which a trial site will be located. In the absence of any objection from the national Competent Authority within 60 days, the CTA will be deemed to have been given. Additionally, approval for the trial protocol must be sought from a Research Ethics Committee before enrolment of any trial subjects can begin. Inevitably, there are variations in the way in which the Clinical Trials Directive has been implemented into national law, leading to a lack of complete harmonisation across the EU. In order to improve the degree of harmonisation and reduce the administrative burden involved in organising cross-border trials in the EU, Regulation (EU) 536/2014 was adopted on 27 May 2014, repealing the Clinical Trials Directive (the “Clinical Trials Regulation”). It entered into force on 16 June 2014, but will take effect no earlier than 28 May 2016. So these upcoming changes did not apply at the time of the Bial trial, which took place under the regime of the Clinical Trials Directive.

Phase 1 clinical trials: “first in man”

Phase I trials, also known as “first in man trials”, are the first stage of testing in human subjects. Normally, a small group of 20–100 healthy volunteers will be recruited. This phase is designed to assess the safety, toxicity, pharmacokinetics[1] and pharmacodynamics[2] of a drug. These clinical trial clinics are often run by contract research organisations (“CROs”) who conduct these studies on behalf of pharmaceutical companies at a dedicated site where participants can be observed by full-time staff and receive 24-hour medical attention and oversight. Phase I trials also normally include dose-ranging studies, also called dose escalation studies to discover the dose at which a compound becomes too toxic to administer. The tested range of doses will usually be a fraction of the dose that caused harm in pre-clinical animal testing. Volunteers are typically paid an inconvenience fee for their time spent in the clinical trials clinic.

The TGN1412 trial

The oversight and monitoring of Phase 1 clinical trials was strengthened in 2007 following a previous tragedy in the UK. Healthy volunteer research subjects suffered multiple organ failure during a first-in-man phase 1 clinical trial at the private clinical trial research centre at Northwick Park Hospital in in 2006. The trial drug, code-named TGN1412, was being developed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, leukaemia and multiple sclerosis. It was administered by injection over a period of minutes, rather than as an infusion over several hours. Following the very serious adverse reactions, the UK Secretary of State for Health convened an Expert Scientific Group under the chairmanship of Professor Gordon W. Duff to investigate and report back with recommendations. The final report of the Expert Scientific group in December 2006 influenced the provision of guidance in July 2007 by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (“CHMP”) of the European Medicines Agency on first-in-human clinical trials (the “EMA Guidance”).

The Bial Trial

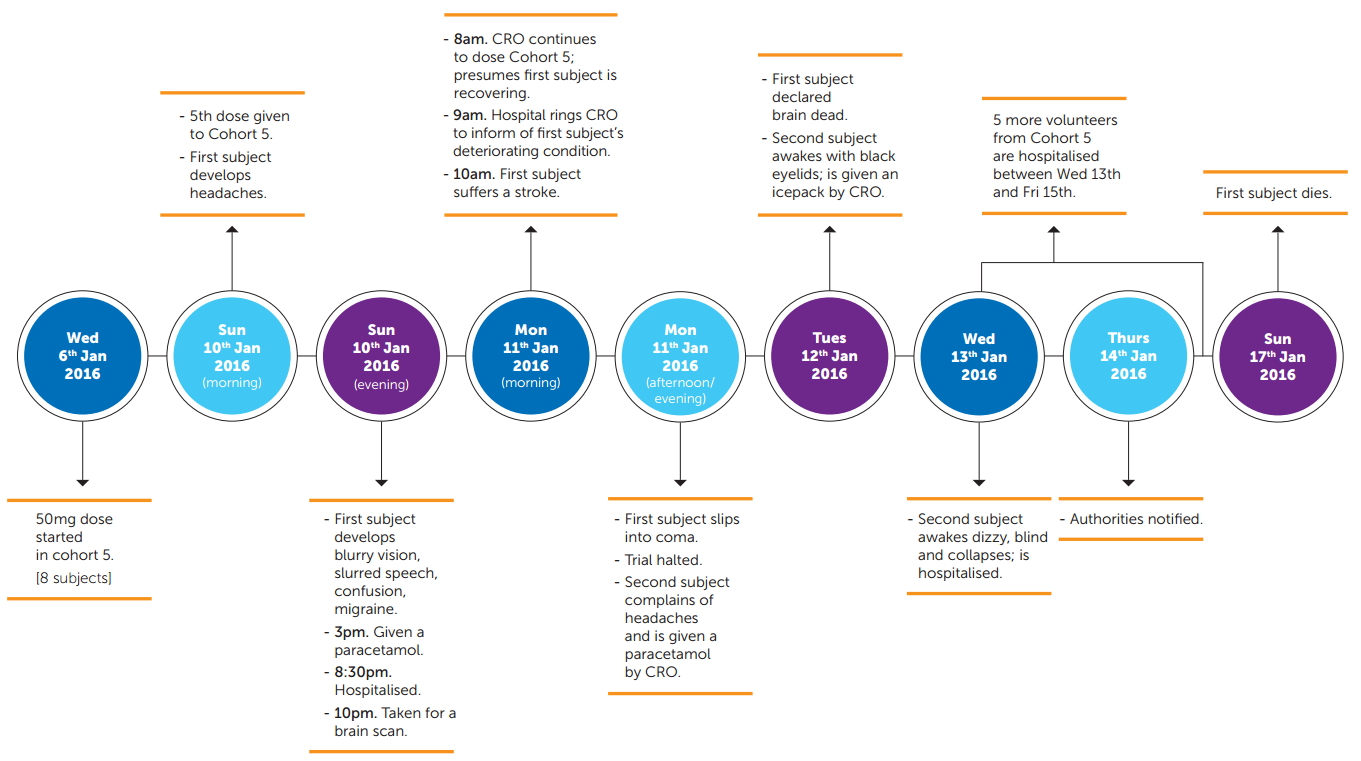

The trial began on 9 July 2015. A CTA application had been filed with the French Competent Authority, the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (“ANSM”), and had received deemed approval. Ethics Committee (“EC”) approval for the trial protocol has also been obtained. The protocol provided for a dose-ranging study in 128 healthy volunteers aged 18—55 years, who were each to be paid €1900. After some single ascending dose studies, four cohorts of volunteers were allocated to multiple ascending dose studies (at 2.5mg, 5mg, 10mg and 20mg). These passed by uneventfully, with no serious adverse events (“SAE”) being reported to the French authorities. A fifth cohort (made up of eight volunteers) was allocated to receive the highest dose (50mg), administered once daily.

On day 5 of dosing this fifth cohort, serious complications began to develop. Within a week, volunteer 2508 (subsequently named as Mr. Guillaume Molinet) tragically died and five other volunteers from the fifth cohort had been left with suspected brain injuries. The only volunteers in the fifth cohort to escape unscathed were the two control subjects who had been administered a placebo. Various French authorities launched formal investigations which are currently underway, including the General Inspectorate of Social Affairs (“IGAS”), the ANSM and the Ministry of Justice. The final reports are not yet available. However, interim reports have been released, which have identified procedural and clinical issues and which shed light on regulatory changes which are likely to follow in France and across the EU.

Key findings – procedural issues

- Delayed trial suspension

Mr Molinet had reported a headache within an hour of being dosed at 8am on day 5 of the study (10 January), and developed significantly slurred speech and double vision by that afternoon. The CRO’s doctor examined him at 3pm, but only prescribed a paracetamol. It was not until the CRO’s staff were challenged by other volunteers concerned by the continuing deterioration in his condition, that he was referred to the local hospital at 8.30pm, where he was admitted as an inpatient. Notwithstanding this SAE, the CRO proceeded to administer another dose of the trial drug to the remaining volunteers at 8am on day 6, without first checking with the hospital on the status of Mr Molinet. Curiously, although the CRO maintains that Mr Molinet had been hospitalised “at the first sign of light symptoms” and that the feedback received from the hospital the previous night had been “re-assuring”, in complete contrast, the letter from the CRO’s onsite doctor referring Mr Molinet to the local hospital describes more serious neurological symptoms (double vision, slurred speech, migraines) that had worsened through that day. The French authorities have criticised the decision not to suspend the trial immediately upon hospitalisation of a previously healthy volunteer with neurological symptoms, after ingesting a high dose of a previously untested drug that was known according to the protocol to interact with the central nervous system.

- Failure to provide appropriate medical care

The second volunteer of the fifth cohort started to complain of similar symptoms on the afternoon of day 6. By this time, Mr Molinet had suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma. Nevertheless, the second volunteer was also only given a paracetamol by the CRO’s doctor. On the morning of day 7, Mr Molinet tragically was declared brain dead and the second volunteer awoke with black eyelids. Nevertheless, the second volunteer was only offered another paracetamol and an ice pack by the CRO’s doctor. It was only on day 8, when the second volunteer collapsed from dizziness, that he was finally hospitalised. The principles of Good Clinical Practice require the Sponsor and CRO to ensure that all volunteers who had taken the drug received appropriate medical attention and follow-up to ensure their safety. The French authorities are concerned that this did not happen, perhaps due to a systemic reluctance on the part of the CRO or Sponsor to acknowledge an emerging pattern.

- Delay in reporting serious adverse event

The hospitalisation of Mr. Molinet occurred on day 6 of the trial, and clearly amounted to a serious adverse events as defined in the Clinical Trials Directive. Due to safety implications, strict reporting obligations require sponsors to be informed by CROs/principal investigators of serious adverse events within 24 hours (paragraph 29, Commission Communication 2001/C 172/01) (the so-called “CT-3” Communication). Hence, CROs tend to have robust measures in place that are triggered as soon as an SAE occurs. This is evidenced by the fact that within hours of the first volunteer slipping into a coma on day 6, Bial and the CRO had agreed to halt the trial. However, the sponsor also has an obligation to notify the national Competent Authority of any suspected, unexpected, serious adverse reaction (“SUSAR”). Where the SUSAR is fatal or life-threating, this must be reported “as soon as possible” and in any event within 7 days after the sponsor is made aware of the case. (paragraph 94, CT-3). Bial eventually notified the ANSM on day 9, four days after the hospitalisation of Mr Molinet. The French authorities are concerned that this did not comply with the obligation to notify “as soon as possible”, even though it was within the seven day longstop. They categorised the delay as a “major failure in the CRO’s crisis management”.

- Failure to obtain informed consent

The Bial informed consent form (“ICF”) presented to every volunteer for signature promised: “You will be informed about any new significant information that could affect your willingness to continue the trial“. The remaining volunteers in cohort 5 were not formally informed of Mr Molinet’s hospitalisation when it happened on day 5, so were never given the opportunity to review their continued participation in the study before the next does of the trial drug was administered at 8am on day 6. While the CRO/Bial were in compliance with EU regulations, they appear to have chosen to ignore the standard set by their own ICF when deciding not to inform the rest of the group regarding the hospitalisation of a participant, before administering them with additional doses. This raises serious ethical concerns.

Key findings – clinical issues

The French authorities have also made various preliminary criticisms about clinical issues, including:

- the volunteer screening (exclusion) criteria did not include a neuro-psychological assessment, even though the trial drug targeted the central nervous system;

- the Sponsor’s pre-clinical animal test data appears to have been insufficient to justify progression to a first-in-man study;

- the dose escalation from 20 mg for the fourth cohort to 50 mg for the fifth cohort was “too sudden”. It is unclear whether the Sponsor presented sufficient pharmacokinetic data to justify this; and

- the choice of 50 mg as the highest does in the dose ranging study was heavily criticised, which was up to 20 to 80 times higher than that needed for the therapeutic mechanism sought to be achieved.

It is unclear why these points were not picked up by either the ANSM or the Research Ethics committee when evaluating the Sponsor’s CTA application. No doubt the full reports of the French Authorities, when they become available, will consider this further.

It is interesting to note that the recommendation in the EMA Guidance as well as similar 2006 recommendations of the French Medicines Agency (AFSSaPS) for allowing sufficient time gaps between dosing of healthy volunteers does not seem to have been followed. Dosing was planned to take place with just 10 minutes between subjects dosed on the same day. Bial has been criticised by French Authorities as well as in an editorial of the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology[3] for not planning sufficient time gaps between dosing of patients.

Regulatory response

The ANSM has already ordered that certain precautionary measure should apply from 31 March 2016 to all trials which it has authorised, including:

- Trial suspension and fresh authorisations. Upon the occurrence of new facts/developments in trials involving healthy volunteers, the trial must be suspended immediately and fresh approvals from authorities must be obtained before resuming the trial.

- Immediate reporting. The timeline for expedited reporting by a sponsor of a SUSAR is shortened from “as soon as possible” to “immediately” reporting obligation to authorities (with the longstop of 7 days unchanged)

- Additional global reporting requirement. Any SUSAR occurring in any other trial anywhere in the world on a related compound, including those conducted by an affiliate company of the sponsor, must be reported by the sponsor immediately to ANSM

- Fresh informed consent: upon the occurrence of new facts/developments in trials involving healthy volunteers, written informed consent must be obtained afresh from every participant before administering further doses to them.

OUTCOMES

- While the trial was conducted in compliance with the letter of the law, it is clear that serious gaps are emerging from both a procedural and clinical viewpoint that require an urgent review of the clinical trials regime under both the Clinical Trials Directive and the Clinical Trials Regulation. Changes to French law and guidance have already been announced, and any sponsors or CROs conducting trials at sites in France will need to implement these changes immediately. Moreover, the EMA has indicated that the findings of the French Authorities could trigger such a revision to EU-wide guidance from the EMA on first-in-man trials. Revisions to the EMA guidance are likely to have global ramifications, as most jurisdictions seek to harmonise trial standards under the influence of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (“ICH”). If the ANSM measures are indicative of this potential EU wide reform, changes can be expected in the areas of robustness of pharmacokinetic data, safety measures, screening criteria, reporting and participant consent for phase 1 trials in particular, but possibly for all trials as well.

[1] Pharmacokinetics is the branch of pharmacology concerned with the rate at which drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolised and eliminated by the body (sometimes also described as what the body does to the drug).

[2] Pharmacodynamics is the branch of pharmacology that studies the effect and mode(s) of action of the drug upon the body.

[3] Br J Clin Pharmacol (2016) 81 582—586.